Last night was my fourth time seeing The Substance. It was also my third time seeing it this month alone. That’s not surprising, as you can tell from an earlier review of mine that I’ve been obsessed since day one. Because Fargeat simply manages to pull off the impossible: creating a darkly funny and horrific satire that seems blunt on the surface, but provides a lot to chew on once you start peeling back all its fleshy layers.

There’s the motif of the colour yellow, representing both the fertility and rebirth found in egg yolk, as well as the destruction and toxicity of pesticides. There’s the overt homages to the Overlook Hotel from The Shining, and Bernard Herrmann’s hauntingly obsessive Vertigo score ** mixed in at the end. While who can forget all the sadly ravaged food on display, which symbolises the ravenous hunger present in the entertainment industry.

Yet, I won’t touch on any of that. Instead, I wish to provide some insight on the ways in which Fargeat explores, not just the Male Gaze, but all forms of perception. It’s clear from the very beginning that the film isn’t just talking about the way others see us, or the way society in general sees women, it also speaks to the way we see ourselves.

Note: Minor plot elements may be spoiled for the sake of highlighting examples, but nothing here will ruin your experience if you haven’t seen the film.

The All-Seeing Eye

Let’s get the most obvious example out of the way first: that ever-present male gaze. Whenever Elisabeth, or her alter ego, Sue record their respective shows, There is almost no studio audience. The crew are barely watching and when people do finally show up for the New Years Eve Show, they are shrouded in matte darkness. What takes their place are spotlights and camera lenses; these cold, oppressive and calculating cyclopses. Even Elisabeth’s next door neighbour is cocooned in the inhuman glass of a peephole when asking, what he believes to be Sue, on a date. I think it’s hard not to see these flashes of mechanical observers as anything other than a stand in for the Male Gaze. The camera will often take control in the more erotic shots of Sue. It will zoom in on her face as she puts a dripping Diet Coke can to her lips, it will rotate around her as it checks out her leathery motorcycle outfit, spinning her round like some rare Barbie doll on display, and it will magnify her arse to be gawked at by the rest of the crew. It’s understandable why a lot of people felt upset with the film, arguing that it was doing the exact objectification it set out to criticise. But that’s the beauty of the film’s over the top nature. By objectifying to such a comical degree, Fargeat is showing you the slight of hand that has been employed by both the entertainment and advertising industries for over a century now. Yes, most of us know it exists, so maybe some felt we didn’t need the primer to begin with, but as I’ll explain further on, I think Fargeat does a fantastic job in highlighting that women are subjected to these images just as much as men are. Men desire the body of the woman on screen, while a lot of women desire to be that woman on screen.

As Above, So Below

After witnessing a test of the titular substance on an egg yolk, we look down from on high as Elisabeth Sparkle’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is built. We see it’s premiere, it’s degradation and its mistreatment. And throughout this montage, people come and go, their opinions of her changing with the passing seasons. And from our vantage point in the sky, having not even seen the woman yet, we already find ourselves judging her character. If the unfeeling camera lens was pure lust, the omniscient view we get from above, and sometimes below, becomes a form of judgement. Regardless of who is on screen, if we are either situated below or above them, we are judging them. It starts off small, we recoil when Elisabeth, now desperate to try the Substance, digs towards us through the trash to find the contact details she so carelessly threw away earlier. Or, we find ourselves looking down on Sue, who, laying on a ruffled silk bedspread, tries her best to grab our attention with an homage to American Beauty, but as we’re not stationed looking up, like Kevin Spacey’s Lester, we’re simply not buying the performance.

However, no group of shots more perfectly encapsulate this feeling of judgement than each of the shower scenes. Every time Sue and Elisabeth switch, there’s an accompanying shower scene. At first, we judge Sue from down low for enjoying her new younger body, and when Elisabeth wakes from her seven day coma for the first time, we judge, from our high ground, the horrific scaring on her spine stemming from a botched stitch job. But as Sue takes up more and more time for herself, and the longer we are stuck judging Elisabeth, we are, by extension, further distancing ourselves from her. By the time she’s reached her breaking point, curled foetal position on the shower floor, the camera raises itself to greater heights and the focal length shifts to create this sense of and endless drop. We feel sorry for Elisabeth, but by the end, it is only a passing pity.

Self-Reflection

If people are constantly judging our looks and actions, it’s hard not to have those same judgements stick with us. This, in the most unfortunate cases, reflects back onto us in the form of an internalised hatred for ourselves and distorts how we view our minds, and most obviously, our bodies. The mirror in Elizabeth’s bathroom becomes the focal point for: 1. moments of discovery (when she first wakes up as Sue), 2. moments of horror (when she looks at her deteriorating body after ‘a slight misuse’ of the Substance), and 3. moments of utter heartbreak (Demi Moore’s particularly poignant portrayal of Elisabeth’s breakdown before her date with the adorkable Fred). All these mirror scenes occur after either Sue or Elisabeth have a full day of hearing what other people have to say or think about them, or it’s after a severe malfunction with the Substance. Fargeat gives us these small pauses, allowing, or in some sense forcing, the audience to take a backseat. This time, the judgement doesn’t come from us, it comes from the characters themselves.

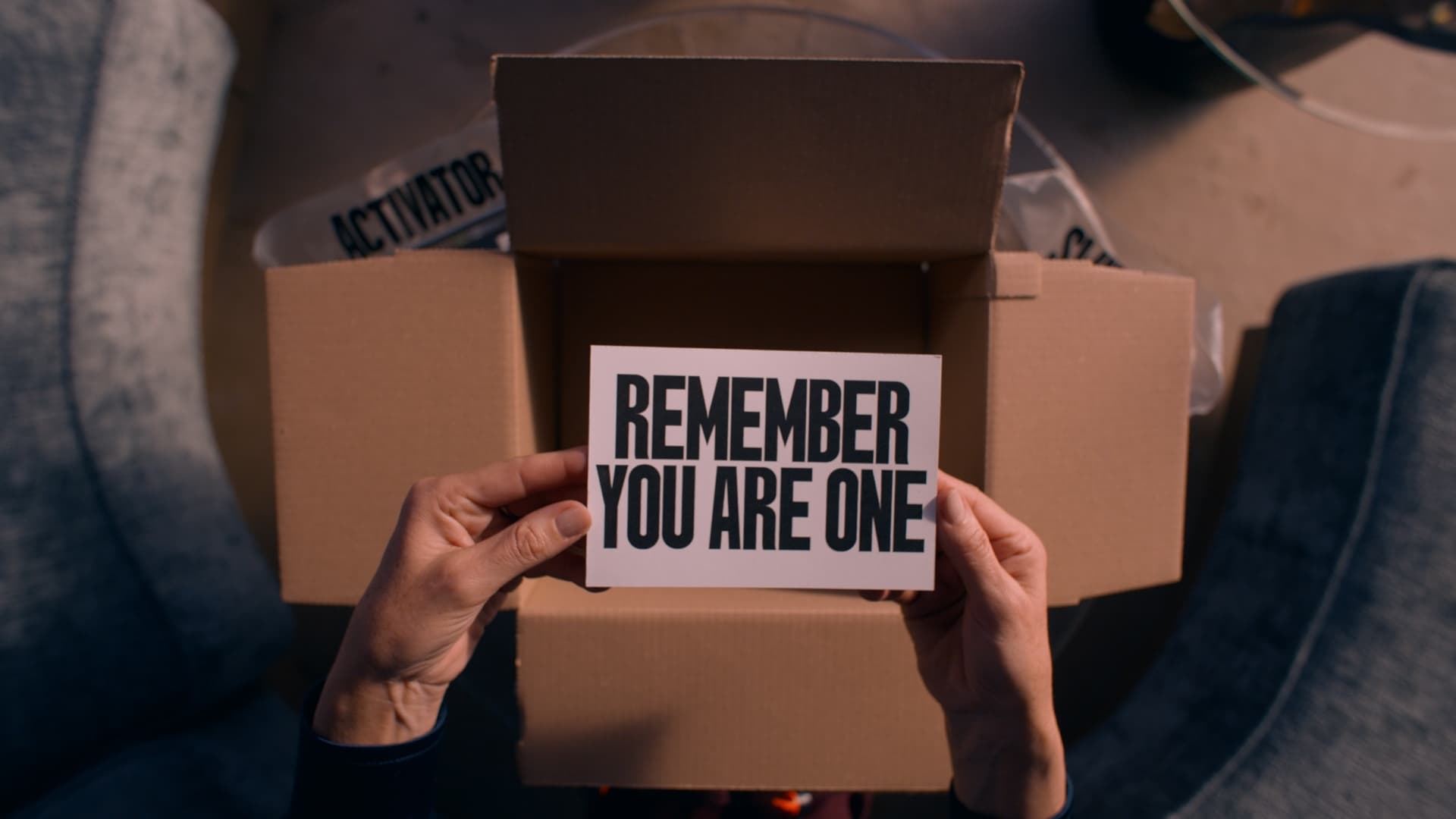

Yet, it’s not just Sue and Elisabeth’s seperate trips to the mirror that make up this portrait of hatred. As the film keeps having to remind both us and them, users of the Substance ‘are one’ and the same. Elisabeth is not viewing Sue’s blown up billboard as a jealous rival to beat, but witnessing the busty and distorted vision of her ideal self. It haunts her every step as she prepares to leave for her date with Fred, and when she stares at her older, more bulbous “reality” in the brass doorknob leading to her hallway, it ultimately destroys her. Meanwhile, Sue can’t bare to look at her old self, choosing to hide away Elisabeth’s larger than life headshot from view of the living room. That’s not to say the older star isn’t guilty of this herself, as she wears big bug eyed shades to avoid people’s gazes, simply so she doesn’t have to see herself reflected in their eyes. Vanity is a symptom of insecurity, which in itself is caused by the people who deem us worthwhile or worthless. Therefore, it’s no wonder Elisabeth and Sue avoid looking at each other – at themselves. Which is why it’s the ultimate irony for both of them that the audience see everything when they use the activator, as the audience can clearly see their contorted forms in the reflection of their pupils.

But seeing is believing, and as much as I like to yap about the movie I implore you to witness this masterpiece for yourselves, especially while you can still watch it in a crowded theatre. Because despite the serious subject matter and gross out moments, I think Fargeat just couldn’t help but make The Substance a real feast for the eyes.