Peter Weir has always been a rather strange director in the Australian canon. He’s a household name, but no one’s quite sure what for? He’s the type of artist whose filmography elicits surprised utterances of, “He made that!?” or “The Cars That Ate what?” But that’s arguably what makes him a talented director, his ability to blend his essence into seemingly anything. At first, you might wonder what an Australian is doing making a film about an American Prep School, yet look a little closer in Dead Poets Society (1989), and you’ll see the Australian Private School experience, complete with Chapel, enigmatic English Teachers, and bagpipes wheezing “Scotland the Brave” every hour on the hour.

No matter how far he strays from our little isolated continent, he always finds a way to take a little piece of home with him on the journey. But what’s that little spark that permeates all of his films? What makes a Weir film a Weir film?

Seeing Dead Poets with Finn, (a friend who happens to share the same name, and not me excusing going to the movies alone) at ACMI, I couldn’t help but comment on how disjointed every one of Weir’s films felt. He has that eye that all great Aussie directors have (Samuel sitting in that field of flowers at the end of Witness (1985) comes to mind) but has that same penchant for meandering in a fairly decent premise, that to most writers, seems rather wasteful. Finn argued that sitting with his characters, like when we hang out in the cave with the boys of Welton Academy as they idly chat, allows us as audiences members to develop a greater investment in the boys when things eventually start moving along.

This makes sense, as another filmmaker might cut away far too quickly for the sake of plot, leaving us wondering if we even knew any of these boys at all. Weir’s storytelling may not be his strong suit, but my God does he have a unique. Everyone of his films carries this much darker undercurrent. That accent of Australian Gothic in Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) – warbling analogue synths, oppressive yet heavenly camerawork, and actors seemingly possessed by some otherworldly force – can be found everywhere in his work. Neil’s late night foray as Puck in Dead Poets will forever be seared into my memory, and the people of Paris and their obsession with road “accidents” were comically frightful. It’s why I can never come away hating one of his films, their is always an image to latch onto, a painting which inspires in me an almost religious fervour that’s difficult to stifle.

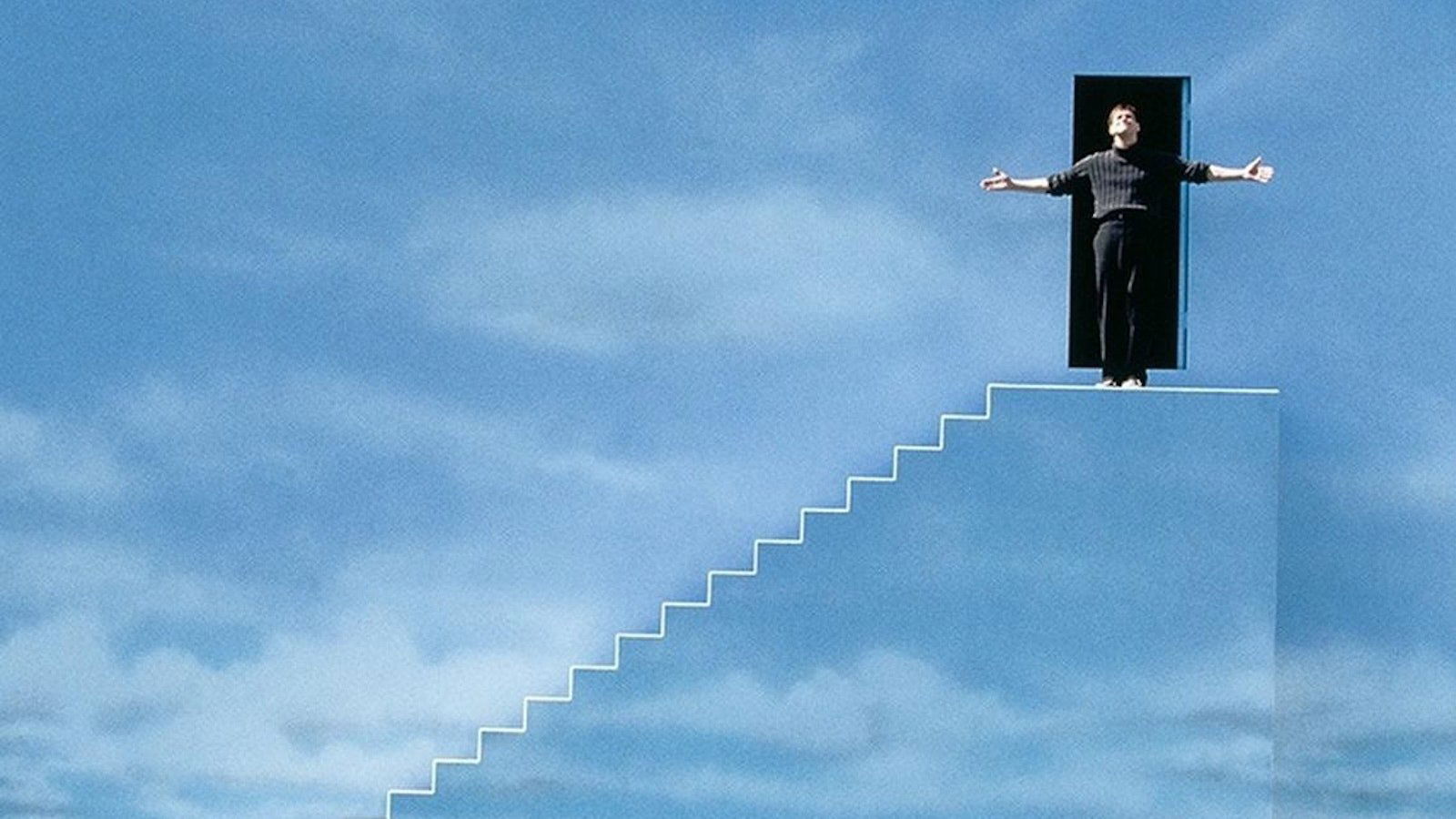

That’s why The Truman Show (1998) is, in my opinion, not only his best film, but the culmination of his greatest qualities as a director. Jim Carrey’s Truman is watched around the clock. Were constantly made aware of the edges of a camera lens as we follow him around the manmade town of Seahaven. We sit behind the newsagent’s desk as he gets the morning paper, we observe him through his car’s steering wheel as he listens to the radio. When Truman snaps, its understandable, but when he begins to hold his supposed wife Meryl hostage, he’s filmed like a psychotic spouse ready to kill. First person shots, dutch angles and hysterics, we see a broken and dangerous man. But what’s far more horrifying is how dismissive director Christof and the rest of the crew are to Truman’s wellbeing, thinking nothing of the time they traumatised him by “killing” his father during a boating accident so that he would not only blame himself, but fear travelling by sea to try and escape the studio. The premise of a round the clock live TV Show suits Weirs ability to sit in a scene, as Truman’s daily routine is filled with seemingly innocuous activities. But thanks to Screenwriter Andrew Niccol, whose world building is always fleshed out, if a little blunt on themes. There’s now an underlying pace to everything. Niccol creates the little hiccups in The Truman Show’s production that start to unravel Truman’s mind. Meanwhile, Weir uses his experience as a director to inform the central theme: a controlling relationship between a creator and his creation only leads to disappointment.

Peter Weir is not a storyteller but a painter. A man concerned more with Film as a form of enlightenment for others than a means of personal catharsis for himself. And while his plots aren’t always the most exciting, his portraits of people and places are wonderfully detailed. His works may not be remembered as solely his, but his art speaks to future filmmakers and creators. Like the spectres of dead poets, each one reaches out to all the artists inside of us and says simply this: “Seize the day!”